Health

Multicenter clinical research supports the safety of deep general anesthesia

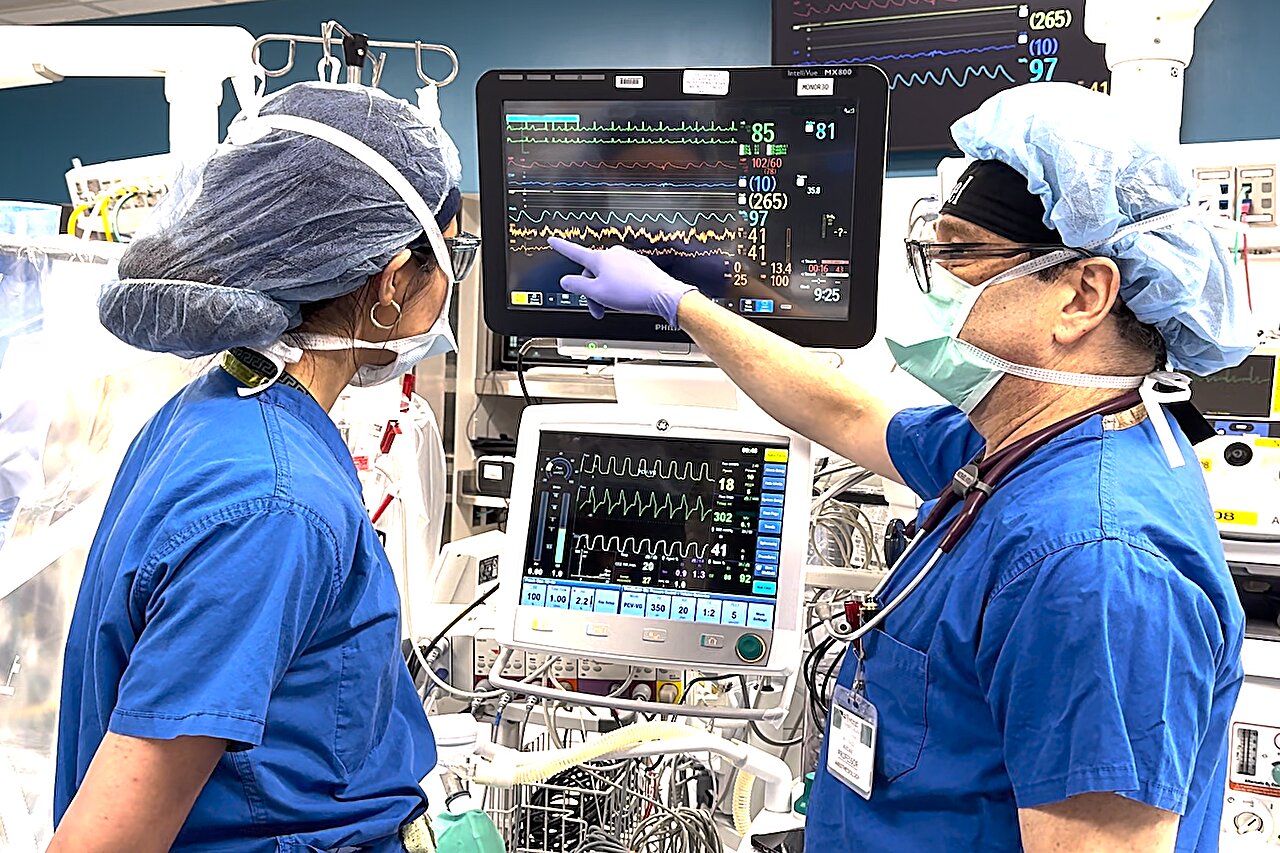

Michael S. Avidan, MBBCh (right), administers anesthesia during surgery. He monitors the electrical activity of the patient’s brain along with chief anesthesiologist Karam Atli, MD, to determine the dosage of anesthesia and ensure that the patient does not inadvertently wake up during surgery. New research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and other institutions supports previous findings indicating that anesthesia at higher doses is no more dangerous to the brain than at lower doses. Credit: Washington University School of Medicine

General anesthesia makes it possible for millions of patients each year to undergo life-saving surgeries while unconscious and pain-free. But the 176-year-old medical staple uses powerful drugs that have fueled fears of adverse effects on the brain, especially when used in high doses.

New findings published on June 10 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), However, support an earlier study indicating that anesthesia at higher doses is no more dangerous to the brain than at lower doses, the researchers said.

The new study reports the results of a multi-center clinical trial involving more than 1,000 elderly patients undergoing heart surgery at four hospitals in Canada. Researchers at these hospitals, working with colleagues at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, found that the amount of anesthesia used during surgery did not affect the risk of postoperative delirium – a condition that can contribute to cognitive decline in the long-term.

“The concern that general anesthesia harms the brain and causes both early and long-term postoperative cognitive impairment is a major reason that older adults avoid or delay life-enhancing procedures,” said Michael S. Avidan, MBBCh, the Dr. Seymour and Rose T. Brown Professor of Anesthesiology and Chief of the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Washington.

“Our new study adds to other compelling evidence that higher doses of general anesthesia are not toxic to the brain. Dispelling the misleading and pervasive message that general anesthesia causes cognitive impairment will have major public health implications by helping older adults help make wise choices regarding essential operations.” , which will promote and sustain healthier lives.”

The dose of anesthesia administered has historically been a carefully calculated balance between too little and too much. Administering an inadequate amount puts patients at risk of unconsciousness during surgery. Despite advances in anesthesia care, approximately one in a thousand people still experience unintentional awakenings during surgery without being able to move or communicate their pain or discomfort. This can lead to suffering and lifelong emotional trauma.

“The good news is that the troubling complication of intraoperative awareness can be prevented more reliably,” said Avidan, senior author of the study.

“Anesthetists can now confidently administer a sufficient dose of general anesthesia, which provides a margin of safety for unconsciousness, without worrying about endangering their patients’ brains. The practice of general anesthesia should change based on increasing reassuring evidence.”

Previous smaller studies have suggested that too much anesthesia could be the cause of postoperative delirium, a neurological problem that includes confusion, altered attention, paranoia, memory loss, hallucinations and delusions. Delirium is a common postoperative complication that affects approximately 25% of elderly patients after major surgery and can be distressing to patients and family members. It is usually temporary but has been associated with longer intensive care unit and hospital stays, other medical complications, persistent cognitive decline and a higher risk of death.

To study the impact of minimizing anesthesia on postoperative delirium, Avidan and colleagues previously conducted a similar clinical trial in more than 1,200 older surgical patients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

The researchers used an electroencephalogram (EEG) to monitor electrical activity in patients’ brains during major surgeries and adjusted anesthesia levels to avoid suppression of brain activity, which is considered a sign of excessive anesthesia levels. They found that minimizing anesthesia administration did not prevent postoperative delirium.

To expand the results of their single-hospital clinical trial, Avidan collaborated with Alain Deschamps, MD, Ph.D., professor of anesthesiology at the Universitè de Montreal in Montreal, and a team of Canadian clinical researchers, to conduct the multicenter trial to be carried out. involving patients at four hospitals in Canada: in Montreal, Kingston, Winnipeg and Toronto.

This randomized clinical trial enrolled 1,140 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, high-risk procedures and a high rate of postoperative complications. In approximately half of the patients, anesthesia was adjusted based on electrical activity in the brain, and in the other group of patients, usual care was provided without EEG monitoring.

The former group was exposed to almost 20% less anesthesia than the latter group and also had 66% less time with suppressed electrical brain activity, but in both groups 18% of patients experienced delirium in the first five days after surgery. Furthermore, the length of hospital stay, the incidence of medical complications and the risk of death up to one year postoperatively were not different between patients in the two study groups.

However, almost 60% more patients in the group who received less anesthesia had unwanted movements during their surgeon’s surgery, which could have negatively affected the operations.

“The thinking was that deep general anesthesia excessively suppresses brain electrical activity and causes postoperative delirium,” Avidan said.

“Taken together, our two clinical trials, which enrolled nearly 2,400 high-risk older surgical patients at five hospitals in the United States and Canada, allay the concern that higher dosing general anesthesia imposes neurotoxic costs. Delirium is likely caused by other factors. then general anesthesia, like the pain and inflammation associated with surgery.

“Future research should explore other avenues to prevent postoperative delirium. But we can now confidently reassure our patients that they can ask for and expect to be unconscious, immobile and pain-free during surgical procedures without having to worry about general anesthesia damaging their brains.”

More information:

Electroencephalography-guided anesthesia and delirium in older adults after cardiac surgery: the ENGAGES-Canada randomized clinical trial, JAMA (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.8144

Quote: Multicenter clinical trial supports safety of deep general anesthesia (2024, June 10), retrieved June 11, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-06-multicenter-clinical-safety-deep-general.html

This document is copyrighted. Except for fair dealing purposes for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.